Historical Research in action: community college bridge program

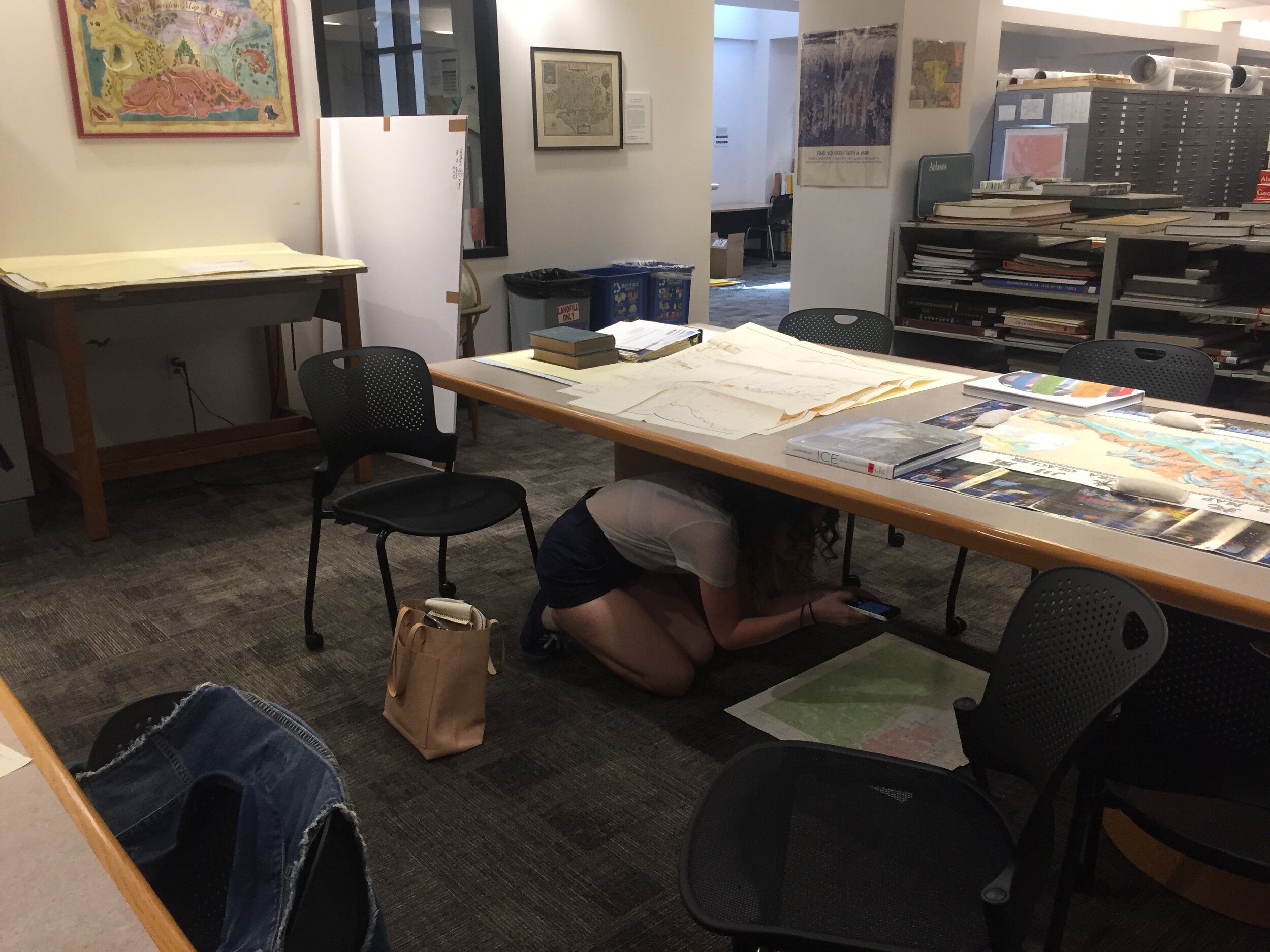

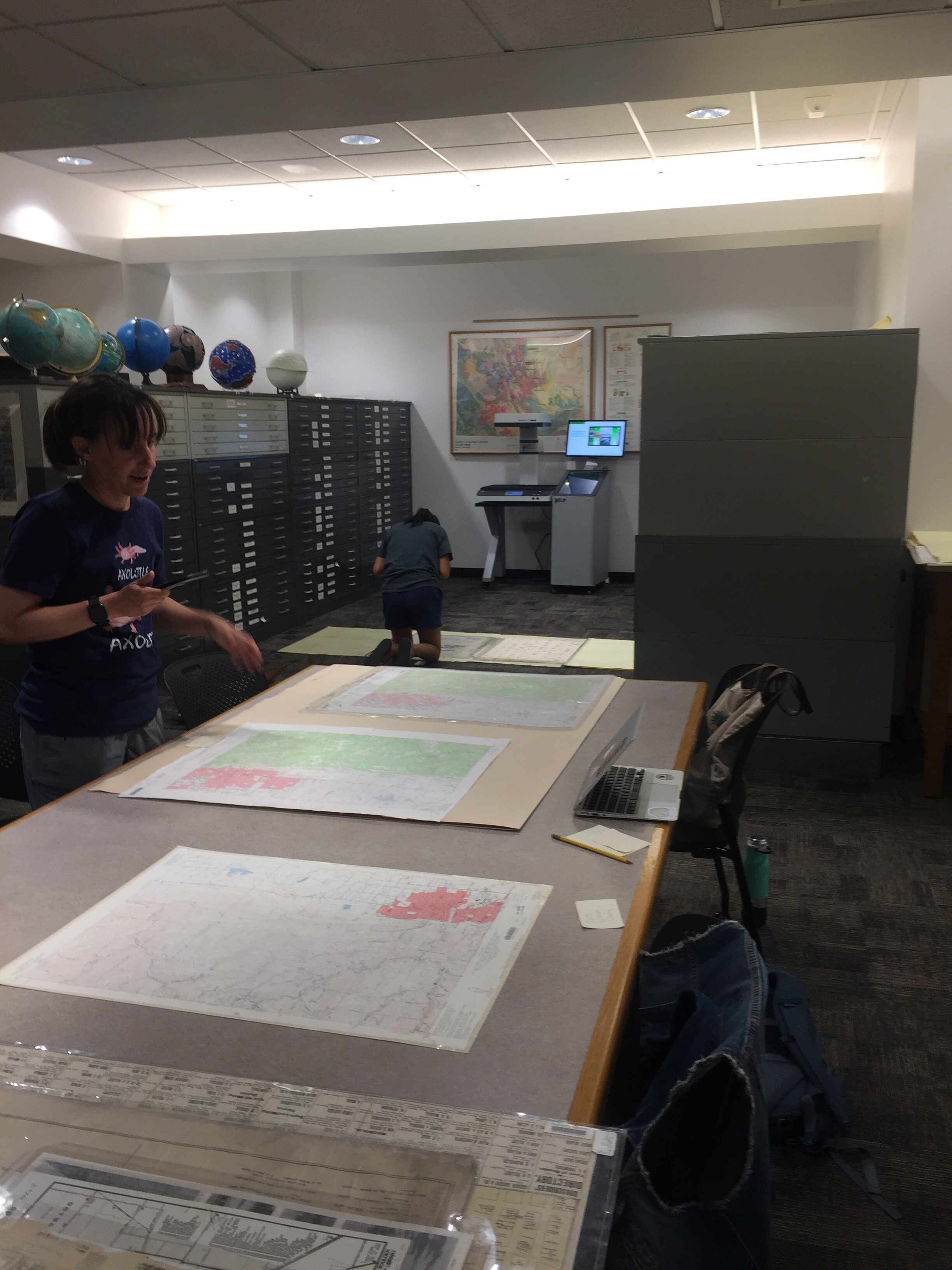

Bridge Program students Allie, Alendra, and Vanessa in the archives at Carnegie Library for Local History in downtown Boulder.

For three weeks in August, members of the Boulder Apple Team Project, community college professors, and community college students transitioning to four-year institutions worked together on scientific and historical research and professional development. This program, called the Bridge Program, was the first of its kind for us and one of the few transition programs for CC students at CU. You can learn more about the program from a previous blog post here.

Three of those students were part of the self-proclaimed ‘history team.’ Together, the four of us practiced surveying an apple tree, interviewing for historical information, and writing summaries of our research. The students spent the majority of their time working with archival documents to research the history of their assigned neighborhoods — the West Pearl area, Old North Boulder, and Hygiene. We went together to the Carnegie Library for Local History in downtown Boulder and the Earth Sciences and Map Library on campus, but the students also took the initiative to visit archives on their own, including the Longmont Archives. Here is what the three of them shared at our end-of-program celebration, paraphrased:

I learned about the dedication that historians need to do research; it’s not just a matter of googling, it takes a network of people, and it is continuous. Those skills are useful beyond history. I learned that past agricultural successes around water, heat, and exposure can help keep the community going in the future. History helps us learn about the “silent voices of scientific discovery.”

“Archives are a treasure.” I loved Carnegie and I loved to “sit in the smell of archival things.”

There is an interconnectedness among the disciplines and historical skills can help scientists talk about their research to non-scientists. Looking back on where we’ve been can help us make informed decisions today.

The map library was a favorite. Leaning over the maps, trying to locate familiar landmarks and find any hint of apple orchards, the students learned about the growth of the city starting with the first plat.

A not-so-favorite experience occurred when I asked each student to spend 45 seconds summarizing the most important points of the 40-plus-page academic articles they read. An important skill — but certainly not a fun one!

These three students are all aspiring scientists, yet they began to fall in love with the history of the neighborhoods they were researching. For one, learning about Joseph Wolff’s abolitionist journalism and the way he “baby-talked” his trees did it. For another, it was the experience of being in the archives among the scraps of history some people had managed to save. For another, it was the usefulness of some historical resources for scientific research.

As the team facilitator, I felt overwhelming gratitude — to my students, to the experts who helped me share the wonders and tools of local history, and to the rest of the BATP team who made the whole program possible.

Amelia Brackett Hogstad